Northern Saints, Saints & Martyrs of our Diocese

St. Cuthbert

Cuthbert was born in North Northumbria in about the year 635 – the same year in which Aidan founded the monastery on Lindisfarne. He came from a well-to-do English family and like most boys of that class, he was placed with foster-parents for part of his childhood and taught the arts of war. We know nothing of his foster-father but he was very fond of his foster-mother, Kenswith. It seems, from stories about his childhood, that he was brought up as a Christian. He was credited, for instance, with having saved by his prayers, some monks who were being swept out to sea on a raft. There is some evidence that, in his mid-teens, he was involved in at least one battle, which would have been quite normal for a boy of his social background.

His life changed when he was about 17 years old. He was looking after some neighbour’s sheep on the hills. (As he was certainly not a shepherd boy it is possible that he was mounting a military guard – a suitable occupation for a young warrior!) Gazing into the night sky he saw a light descend to Earth and then return, escorting, he believed, a human soul to Heaven. The date was August 31st 651AD – the night that Aidan died.

Perhaps Cuthbert had already been considering a possible monastic calling but that was his moment of decision. He went to the monastery at Melrose, also founded by Aidan, and asked to be admitted as a Novice. For the next 13 years he was with the Melrose monks. When Melrose was given land to found a new monastery at Ripon, Cuthbert went with the founding party and was made guestmaster.

In his late 20s he returned to Melrose and found that his former teacher and friend, the prior Boisil, was dying of the plague. Cuthbert became prior (second to the Abbot) at Melrose. In 664AD the Synod of Whitby decided that Northumbria should cease to look to Ireland for its spiritual leadership and turn instead to the continent the Irish monks of Lindisfarne, with others, went back to Iona. The abbot of Melrose subsequently became abbot of Lindisfarne and Cuthbert its prior.

Cuthbert seems to have moved to Lindisfarne at about the age of 30 and lived there for the next 10 years. He ran the monastery; he was an active missionary; he was much in demand as a spiritual guide and he developed the gift of spiritual healing. He was an outgoing, cheerful, compassionate person and no doubt became popular. But when he was 40 years old he believed that he was being called to be a hermit and to do the hermit’s job of fighting the spiritual forces of evil in a life of solitude. After a short trial period on the tiny islet adjoining Lindisfarne he moved to the more remote and larger island known as ‘Inner Farne’ and built a hermitage where he lived for 10 years. Of course, people did not leave him alone – they went out in their little boats to consult him or ask for healing.

However, on many days of the year the seas around the islands are simply too rough to make the crossing and Cuthbert was left in peace. At the age of about 50 he was asked by both Church and King to leave his hermitage and become a bishop. He reluctantly agreed. For two years he was an active, travelling bishop as Aidan had been. He seems to have journeyed extensively. On one occasion he was visiting the Queen in Carlisle (on the other side of the country from Lindisfarne) when he knew by second sight that her husband, the King, had been slain by the Picts doing battle in Scotland.

Feeling the approach of death he retired back to the hermitage on the Inner Farne where, in the company of Lindisfarne monks, he died on March 20th 687AD.

St.Cuthbert died on the Inner Farne island and was buried on Lindisfarne. People came to pray at the grave and then miracles of healing were claimed. To the monks of Lindisfarne this was a clear sign that Cuthbert was now a saint in heaven and they, as the saint’s community, should declare this to the world.

In those days people felt it important, when they prayed for help or healing, to be as close as possible to a saint’s relics. And so, if a community made relics available that was equivalent to a declaration of sainthood. The monks of Lindisfarne determined to do this for Cuthbert.

They decided to allow 11 years for his body to become a skeleton and then ‘elevate’ his remains on the anniversary of this death (20th March 698). We believe that during these years the beautiful manuscript known as ‘The Lindisfarne Gospels’ was made, to be used for the first time at the great ceremony of the Elevation. The declaration of Cuthbert’s sainthood was to be a day of joy and thanksgiving. It turned out to be also a day of surprise, even shock, for when they opened the coffin they found no skeleton but a complete and undecayed body. That was a sign of very great sainthood indeed.

So the cult of St.Cuthbert began. Pilgrims began to flock to the shrine. The ordinary life of the monastery continued for almost another century until, on 8th June 793, the Vikings came. The monks were totally unprepared; some were killed; some younger ones and boys were taken away to be sold as slaves; gold and silver was taken and the monastery partly burned down. After that the monastery lived under threat and it seems that in the 9th century there was a gradual movement of goods and buildings to the near mainland.

The traditional date for the final abandonment of Lindisfarne is 875 AD.

The body of St.Cuthbert, together with other relics and treasures which had survived the Viking attack were carried by the monks and villagers onto the mainland.

For over 100 years the community settled at the old Roman town of Chester-le-Street. It was said that fear of further attack took them inland to Ripon but not for long and on their journey back from there they finally settled at Durham.

After the Norman Conquest (1066) a Benedictine community replaced the “St.Cuthbert’s Folk” and began to build the great Norman cathedral at Durham. They proposed to honour the body of St.Cuthbert with a new shrine immediately east of the new High Alter and in 1104 the placed was ready.

At this point, it seems spurred on by doubts expressed by others about the truth of the tradition of the undecayed body, the Durham monks opened up the coffin and found, so it was said, that the body was indeed still uncorrupt. Throughout the Middle Ages the coffin was placed in a beautiful shrine and visited by great numbers of pilgrims. But at the reformation, when the monastery was dissolved, the shrine was dismantled and the coffin opened – it seems that the body was still complete.

It was buried in a plain grave behind the High Altar. In 1827 the coffin was again opened and a skeleton was found. The objects in the coffin were removed and can now be seen in the Cathedral treasury. The human remains were reburied. In 1899 the coffin was again opened and a doctor carried out a post-mortem on the remains. His opinion was that the skeleton was consistent with all that is known of St.Cuthbert in his lifetime.

The human remains were then re-interred in the same place and marked by a plain gravestone with the name Cuthbertus. This feretory, as it is called, is still the site of many pilgrimages today.

St Cuthbert’s feast is kept on the 20th of March

St. Oswald

Queen Aacha took her children to the Court of Dalriadan King, Eochaid Buide, at Dunadd in modern Scotland. Here, the family was converted to Christianity by monks from Iona Abbey and Oswald and his brother, Oswiu, were sent to the same monastery to be educated. Little is known of these formative years in the far North, but it does appear that Oswald became a brave warrior at an early age, accompanying King Connad Cerr of Dalriada to Ireland to fight against Maelcaich and the Irish Cruithne at the Battle of Fid Eoin in AD 628.

While Oswald was growing up, his old enemy, King Edwin, had been waging a major war against the allied forced of Gwynedd and Mercia. In AD 633, he was killed in battle and Oswald’s elder half-brother, Eanfrith, was able to establish himself on the Bernician throne for a almost a year. However, he was just as unpopular with the Northern Welsh and the Mercians who were prompt in his cature and execution. Despite have a baby son still exiled in Pictland, Oswald clearly saw himself as his brother’s heir, probably with encouragement from the Northumbrians. As his father was Bernician and his mother, Deiran, he was one of the few people who could unite the Kingdom.

Having been lent a small force of men by King Domnall Brecc of Dalriada (including monks from Iona), Oswald marched south to claim his inheritance. He clashed with King Cadwallon of Gwynedd at the Battle of Heavenfield. Oswald raised a large cross their before the fight and the prayers of his soldiers around it are said to contributed to the King’s victory, despite the superior numbers of the Welsh army. Triumphantly he marched into York, while the Dowager Queen Ethelburga of Deira and her family fled from Yeavering and the new King’s expected wrath.

Oswald’s reputation as a saint originates in his re-introduction of Christianity to Northumbria. The chief among the monks who accompanied him from Dalriada initially attempted to convert the Northumbrians, but met with little success. So Oswald sent to the monks of Iona for an evangelical Bishop. St. Aidan, Bishop of Scattery Island in Ireland, arrived the following year and set up a strong missionary movement centred on Lindisfarne, near the

Royal Court at Bamburgh. It was at the latter that the famous legend took place which resulted in St. Aidan blessing the King’s arm and making it incorruptable, even in death. King Oswald himself often acted as an ecclesiastical interpreter, for the new Northumbrian Bishop who spoke only Gaelic.

Oswald further increased the spread of Christianity in Britain by pressurizing King Cynegils of Wessex to allow St. Birinus to preach to his people. Oswald eventually agreed to a strategic alliance with the southern king, cemented by his marriage to Cynegils’ daughter and the latter’s baptism with Oswald standing as Godfather.

Such bonds were important to Oswald and he did not forget his old allies, the Dalriadan Kings, who had helped him gain his throne. For he appears to have sent troops to Ireland to assist King Domnall Brecc and his ally, King Congal Caech of Ulster, during the Irish dynastic wars. By AD 638, Oswald was in a secure position at home and he turned to expansionism. His army moved north and besieged and captured Edinburgh. Then, in a stroke of, what appears to have been, diplomatic genious, he arranged for his brother, Prince Oswiu, to marry Princess Rhiainfelt, the last remaining heiress of North Rheged. The old Celtic kingdom was subsequently swallowed up by Northumbria in a peaceful takeover. Oswiu continued to expand the kingdom’s borders by taking his brothers armies to Gododdin and conquering modern lowland Scotland as far north as Manau. Bede claims that the King was thus recognised as Bretwalda by all of Saxon England.

There were, however, forces gathering who wished to bring to an end King Oswald’s glorious reign in Britain. In AD 642, the old Northumbrian enemy, King Penda of Mercia gathered a large united Welsh and Mercian force against King Oswald. The Welsh contingent included the armies of Gwynedd, Powys and Pengwern. They clashed at Maserfield, now Oswestry (Oswald’s Tree) in Shropshire, and Oswald was killed.

King Oswald’s body was hacked to pieces by the victors and his head and arms stuck on poles. An old legend has one arm taken to his sacred ash tree (Oswald’s Tree) by his constant companion, a pet raven. Where it fell a holy well sprang up. Thus, Oswald came to be reverred as a Christian martyr and his dismembered limbs eventually found there way into various relic collections in monasteries around the country. His body was removed to Bardney Abbey and later translated to St. Oswald’s in Gloucester.

The King’s Royal Standard of purplish-red and gold, once to be seen at Bardney (and probably the banner which found its way to Durham), forms the basis of the coat of arms of modern Nothumberland. Popular iconography depicts the King wearing a crown and carrying sceptre and orb, the ciborium (showing his charity to the poor), a sword, a palm-branch or his raven companion.

St Aidan

However, when Edwin was killed in battle by the pagan Penda of Mercia, Christianity was driven underground until Oswald became King. Oswald had been educated on Iona as a boy, and had become a Christian there.

Before the battle in which he gained the crown, he set up a rough wooden cross on the battle field, to show that he was fighting for the Christian faith as well as for a kingdom. So naturally as King he turned to Iona to supply him with a missionary bishop to preach to his people.

The first missionary sent from Iona said the Northumbrians were “uncivilised people of obstinate (stubborn) and barbarous temperament” (brutal anger) and returned home disgusted. The Ionan monks then chose the wise and gentle Aidan to make the second attempt. He was consecrated (blessed) bishop and sent to Northumbria in 634.

St Aidan chose Lindisfarne as his missionary centre. Here his monks could have found seclusion (be alone) due to the high tides but they could easily walk across the sands at low tide to the King’s house at Bamburgh and to the mainland.

None of the buildings from the Celtic monastery remain today. They were probably small, round wooden huts with thatched roofs, Churches within the monastery would also have been small. St Aidan’s monastery may have been on the Heugh, or in the place where the stone ruins of the Benedictine Priory may still be seen. St Aidan realised from the start the importance of a “native Priesthood” learning school on Lindisfarne was one of the many important things he did. Boys were taught to read and write, and the Latin they needed for the Gospels and Psalms. They were trained as Priests and missionaries. Many of them became famous, and much of England was converted (became Christian) by them.

St Aidan also started the monastic (Nun) life for women of Northumbria. Under his guidance St Hilda became the first great Abbess, ruling houses at Hartlepool and Whitby. So women had the chance to give themselves to God in a life of prayer and service. But they did not go go out as travelling missionaries in the same way as the men. St Aidan always travelled around by foot. He comforted the poor and attacked the rich.

St Aidan spent much of his time reading the scriptures and learning Psalms. Aidan introduced the custom of fasting until 3 o’ clock in the afternoon on Wednesdays and Fridays throughout the year except during the forty days after Easter. Many miracles were claimed to have been done by Aidan.

One of the best known involves a Priest called Utta who was to travel to Kent by sea and asked Aidan to pray for him. Aidan prophesied (predicted) a storm and gave Utta some oil, telling him to cast it upon the waves when the storm broke. As prophesied a storm overwhelmed the ship and all had given up hope when Utta poured the oil on the waters and the storm died down.

Loved and respected by all St Aidan died at Bamburgh in 651, after 17 years as the first bishop of Lindisfarne. His feast day is 31st August

St Bede

He was the first person to write scholarly works in the English language, although unfortunately only fragments of his English writings have survived. He translated the Gospel of John into Old English, completing the work on the very day of his death. He also wrote extensively in Latin. He wrote commentaries on the Pentateuch and other portions of Holy Scripture. His best-known work is his History of the English Church and People, a classic which has frequently been translated and is available in Penguin Paperbacks.

It gives a history of Britain up to 729, speaking of the Celtic peoples who were converted to Christianity during the first three centuries of the Christian era, and the invasion of the Anglo-Saxon pagans in the fifth and sixth centuries, and their subsequent conversion by Celtic missionaries from the north and west, and Roman missionaries from the south and east.

His work is our chief source for the history of the British Isles during this period. Fortunately, Bede was careful to sort fact from hearsay, and to tell us the sources of his information.

He also wrote hymns and other verse, the first martyrology with historical notes, letters and homilies, works on grammar, on chronology and astronomy — he was aware that the earth is a sphere, and he is the first historian to date events Anno Domini, and the earliest known writer to state that the solar year is not exactly 365 and a quarter days long, so that the Julian calendar (one leap year every four years) requires some adjusting if the months are not to get out of step with the seasons.

St Hilda of Whitby

She lived the life of a noblewoman until 20 years later when she was moved by the example of her sister Saint Hereswitha who became a nun at the Chelles Monastery in France. Hilda intended to follow her sister abroad, but St. Aidan persuaded her to return to Northumbria in 649. She was initially put in charge of a small group of women who were also aspiring to the religious life at a small house on the River Wear, but Bishop Aidan soon realized she was ready for wider responsibilities. There was a much larger and fully established religious house of women at Hartlepool whose Foundress, Bega (St. Bee), was founding a new house at Tadcaster. Hilda was called to take her place as Superior. St. Hilda ruled at Hartlepool for some years with great success before being called to found a monastery at Streaneshalch, a place to which the Danes a century or two later gave the name of Whitby.

St. Hilda governed the monastery at Whitby for the rest of her life. Under Abbess Hilda, Whitby gained a great reputation, becoming a burial place for kings, and a place of pilgrimage. The fame of St. Hilda’s wisdom was so great that from far and near monks and royal personages came to consult her. Whitby was also a double monastery: a commu nity of men and another of women, with the chapel in between, and Hilda as the governor of both. It was a great center of learning, especially the study of sacred scripture. Whitby was known as a place where clergy, monks and nuns could receive a rigorous and thorough religious education. The arts and sciences were so well established by her that it was regarded as one of the best seminaries for learning in the then known world. No less than five of her subject monks later became bishops, including Saint John of Beverly, and Saint Wilfrid of York.

St. Hilda was especially revered for her ability to recognize spiritual gifts in both men and women. Her kindheartedness can be seen from the story of Caedmon, one of her herdsmen, whose poetic gift was discovered and nurtured by Hilda. She encouraged him with the same zeal and care she would use toward a member of the nobility, urging him to use his gifts as a means of bringing the knowledge of the Gospel Truth to common folk. St. Caedmon later composed the first hymns in the English language.

Whitby Abbey stands at the very crossroads of Celtic and Roman Christianity. Roman and Celtic traditions differed, not in basic doctrine, but on such questions as the proper way of calculating the date of Easter, and the proper style of haircut and dress for a monk. It was highly desirable that Christians in the same area should celebrate Easter at the same time; and eventually the Church had to choose between the Celtic customs it had inherited from before 300, and the customs that missionaries had brought from continental Europe and Rome. It was at Whitby Abbey in 663 when King Oswy, persuaded by the arguments of St. Wilfrid, convened a synod to decide once and for all the date of the observance of Easter, and resolve other differences between Celtic and Roman ecclesiastical practices. Saint Hilda was a strong supporter of the Celtic party, nevertheless, once the Synod of Whitby decided to observe the Roman rule and customs, Hilda used her moderating influence in favor of its peaceful acceptance. This period of conflict over the Easter observance was a time of great discord in the religious communities. Hilda’s influence, persuading her followers to adhere to the decision, was one of the key factors in securing unity in the Church.

The Venerable Bede is enthusiastic in his praise of Abbess Hilda, one of the greatest women of all time: She was the adviser of rulers as well as of ordinary folk; she insisted on the study of Holy Scripture and proper preparation for the priesthood; the influence of her example of peace and charity extended well beyond the walls of her monastery; and “all who knew her called her Mother, such were her wonderful godliness and grace.” Saint Hilda is often represented in art holding Whitby Abbey in her hands with a crown on her head or at her feet. Sometimes she is shown turning serpents into stone; stopping the wild birds from ravaging corn at her command; or as a soul being carried to heaven by the angels. Frequent historic place-name references to Shields are probably sites named after her, Shields being thought to be a corruption of St. Hilda.

Seven years before her death St. Hilda was stricken down with a fever which never left her till she breathed her last. In spite of this, she neglected none of her duties to God or to her subjects. She passed away most peacefully after receiving the Holy Communion and Anointing, and the tolling of the Whitby monastery bell was heard miraculously thirteen miles away, where Saint Bee saw the soul of St. Hilda borne to heaven by angels. Hilda remained a peacemaker to the very end-her greatest concern was that her monastic family should be one in the Lord, and her last recorded words were: “Have evangelical peace among yourselves.” She died on November 17, 680.

St. Wilfrid

Born in Northumberland in 634, St. Wilfrid was educated at Lindesfarne and then spent some time in Lyons and Rome. Returning to England, he was elected abbot of Ripon in 658.

In 664, he was the architect of the definitive victory of the Roman party at the Synod of Whitby. He was appointed Bishop of York and after some difficulty finally took possession of his See in 669. He laboured zealously and founded many monasteries, but he was obliged to appeal to Rome in order to prevent the subdivision of his diocese by St. Theodore, Archbishop of Canterbury. While waiting for the case to be decided, he was forced to go into exile, and worked hard and long to evangelize the heathen south Saxons until his recall in 686.

In 691, he had to retire again to the Midlands until Rome once again vindicated him. In 703, he resigned his post and retired to his monastery at Ripon where he spent his remaining time in prayer and penitential practices, until his death in 709. St. Wilfrid was an outstanding personage of his day, extremely capable and possessed of unbounded courage, remaining firm in his convictions despite running afoul of civil and ecclesiastical authorities. He helped bring the discipline of the English Church into line with that of Rome. He was also a dedicated pastor and a zealous and skilled missionary; his brief time spent in Friesland in 678-679 was the starting point for the great English mission to the Germanic peoples of continental Europe. His feast day is October 12th.

Wilfrid is said to have donated land upon which Preston was founded – Priest Town. In fact, St Wilfrid’s coat of arms – the Lamb & Flag – are used Preston’s City Council as part of the city’s crest. Preston – from Anglo-Saxon Preost Tun – means settlement of the Priest.

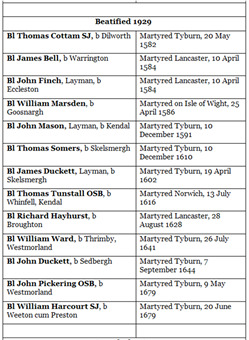

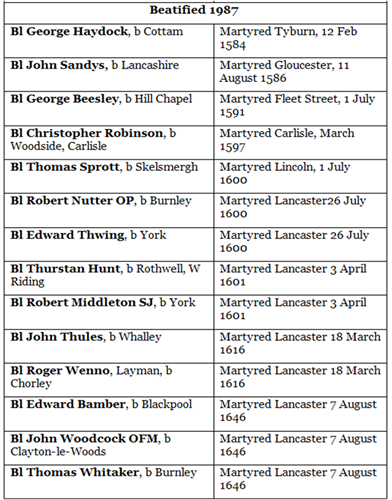

CANONISED and BEATIFIED MARTYRS

LINKED WITH THE AREA COVERED BY THE PRESENT DAY DIOCESE OF LANCASTER

The Catholic Martyrs of the English Reformation are men and women who died for the Catholic faith in the years of persecution between 1534 and 1680. A certain number of them have officially been recognised as martyrs by the Catholic Church.

Catholics in England and Wales were executed under treason laws. On 25 February 1570 Pope Pius V’s “Regnans in Excelsis” bull excommunicated both the English Queen Elizabeth I and any who obeyed her. This papal bull also required all Roman Catholics to rebel against the English Crown as a matter of faith. In response in 1571 legislation was enacted making it treasonable to be under the authority of the Pope, including being a Jesuit, being Roman Catholic or harbouring a Catholic priest. The usual penalty for all those convicted of treason at the time was execution by being hanged, drawn and quartered.

As early as the reign of Pope Gregory XIII (1572–85), authorisation was given for 63 recognised martyrs to have their relics honoured and pictures painted for devotion. These martyrs were formally beatified by Pope Leo XIII, 54 in 1886 and the remaining nine in 1895. Further groups of martyrs were subsequently documented and proposed by the bishops of England and Wales, and formally recognised by Rome.

The following martyrs are associated with the territory now under the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Lancaster: